Co-founder of Temperaturas Extremas Arquitectos

PAST

GV: Could you describe the initial years of your career? How did you choose to study this profession? What are the most important moments you remember from those years?

AA: First of all, I didn’t want to be an architect, it was only a possibility. In fact, here in Spain, when we have to decide careers, we have to put in three options. On the day of our registration, I had, in this order: Philosophy, Medicine and Architecture. When I arrived home with this paper, my parents asked me which one of the three I would choose. I said, “Architecture.” When they asked why, I said, “Because it starts with an ‘A’.” This just shows that I really was not obsessed with architecture from a young age. However, I do remember that when I was very young, in school, a group of psychologists made us take a test one day and what’s interesting is that they told me that my test results indicated that I should become an architect. When I asked them why, they responded, “You can’t be with people. You must work alone in a space with nobody around you, because you are quite a conflictive person.” This is relevant because 50 years later, I notice that the profession has changed drastically. Back then, the architect was a man, alone in his office, away from society and their needs. Now we are part of society, as agents of a global world. Perhaps I studied architecture because I liked to be alone but now I am with people all day and everywhere. Since the first day, I can say that this was my home. We were part of less than 10% of women; 14 girls in my class of around 200 to 250 people. I didn’t notice the difference, because it was very common at that time in Spain that women didn’t have access to these kinds of careers. I felt very good during my entire career, so when I finished my studies, I decided to become a teacher.

«Now we are part of society, as agents of a global world. Perhaps I studied architecture because I liked to be alone but now I am with people all day and everywhere. Since the first day, I can say that this was my home.»

GV: From that point when you finished your studies till today, can your career be described through phases or perhaps certain important moments that defined your career?

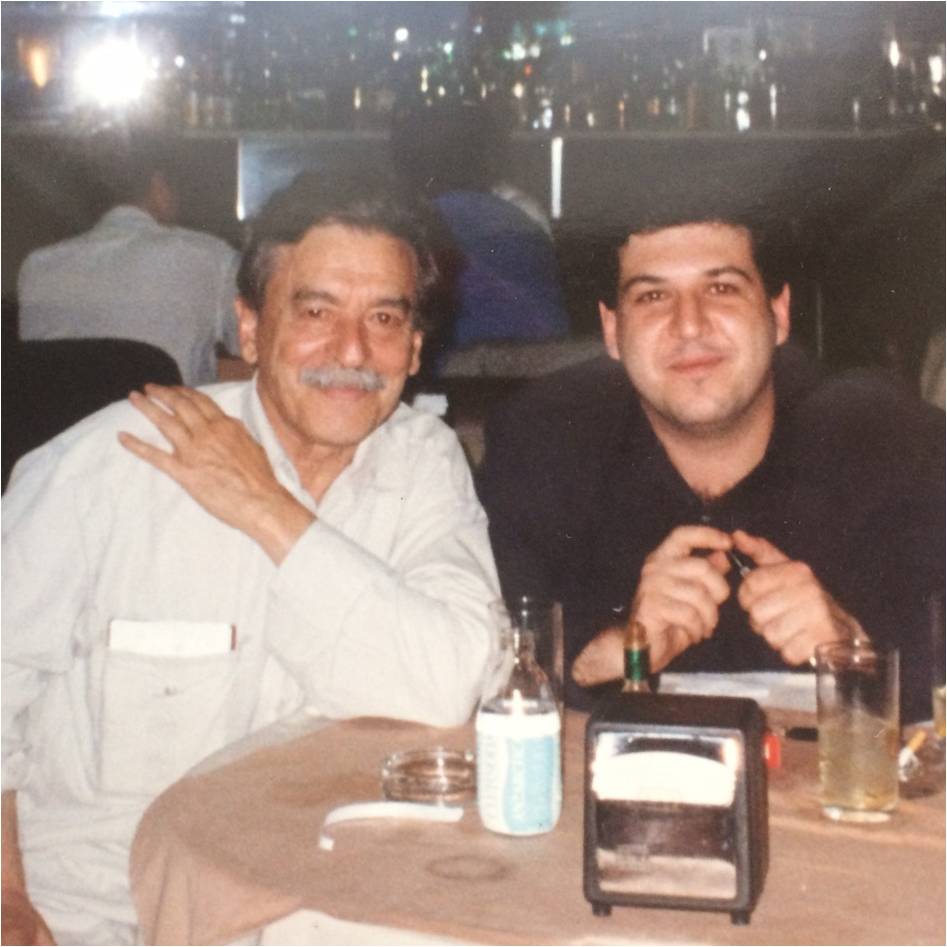

AA: Yes, when one gets older, they often reflect about their past and you will find points in your personal story or history that are very important for the future. One such moment was when we started Temperaturas Extremas. I met Nicolás when I joined university. Eight months later in June, I told him, “Nicolás, I want to start a studio with you.” That year, we founded our office and participated in our first competition. Needless to say, we got placed last because it was in Japan. Sometimes, when we think about it, we ask ourselves why when we were eighteen, did we suddenly decide to form a group, to work, to hire a space and to participate in an international competition. It was absolutely surrealist. We would keep trying these surrealist competitions, struggling against top architects that are very well known in Spain, a very closed circle. Later, I met Andrés, who is now my husband. It was when I fell in love that I asked him, “Hey, do you want to come work with us?” There were some conflicts, obviously, but in the end, the practice was formed. So, it began thirty years ago out of love, but it was also the need to innovate, to get our ideas out, and to combine different things, and it is still the same now. Now when we work as three friends with a very affectionate connection, which means that we can fight and argue on one day and on another, we do a competition. Back then, we were amateurs who didn’t know anything about the future. Another important moment was after my PhD research. Initially, I studied the industrial design of the 60s but the focus changed from the kitchen to a gender issue. It was the first work here in the department of projects with a focus on gender. Since then, I have been linked to the gender approach in everything: in our competitions, in our teaching, in the Biennale, and everywhere else. These were the most important moments during the trajectory of my career in architecture.

GV: How do you think the teaching environment has changed throughout your entire career? Do you see a different way to approach the students?

AA: I really wish I could be positive in my answer, but things have changed. I doubt that it is moving in a good direction. Bureaucracy has consumed universities and now there are two kinds of teachers. One kind are those who want to be “teaching officials” and want to rise in their career step by step. They don’t have time to practice as professional architects; not just in building, but making films, writing articles, or giving speeches about the city. When I studied, they were usually all men and were all practicing architecture, so what they taught us was how to be an architect through the practice. The second kind of teachers were those for whom theory and research was mixed. While some of them lose touch with their practice, to me, it is very i the same responsibility with the world around us because in the end you are all of them: a teachemportant that teaching, research, and design are absolutely linked and not separated. I haver, an architect and a researcher.

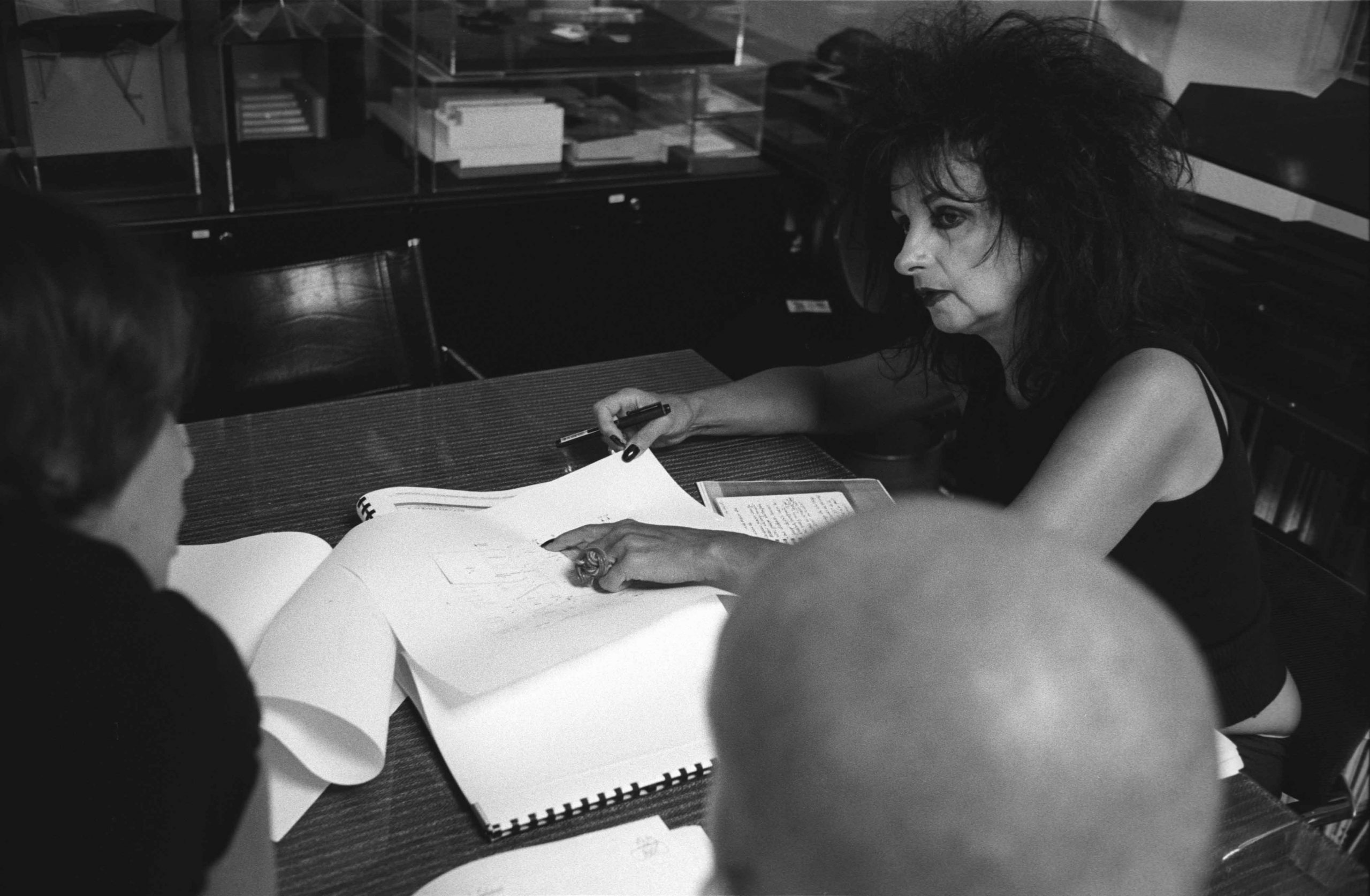

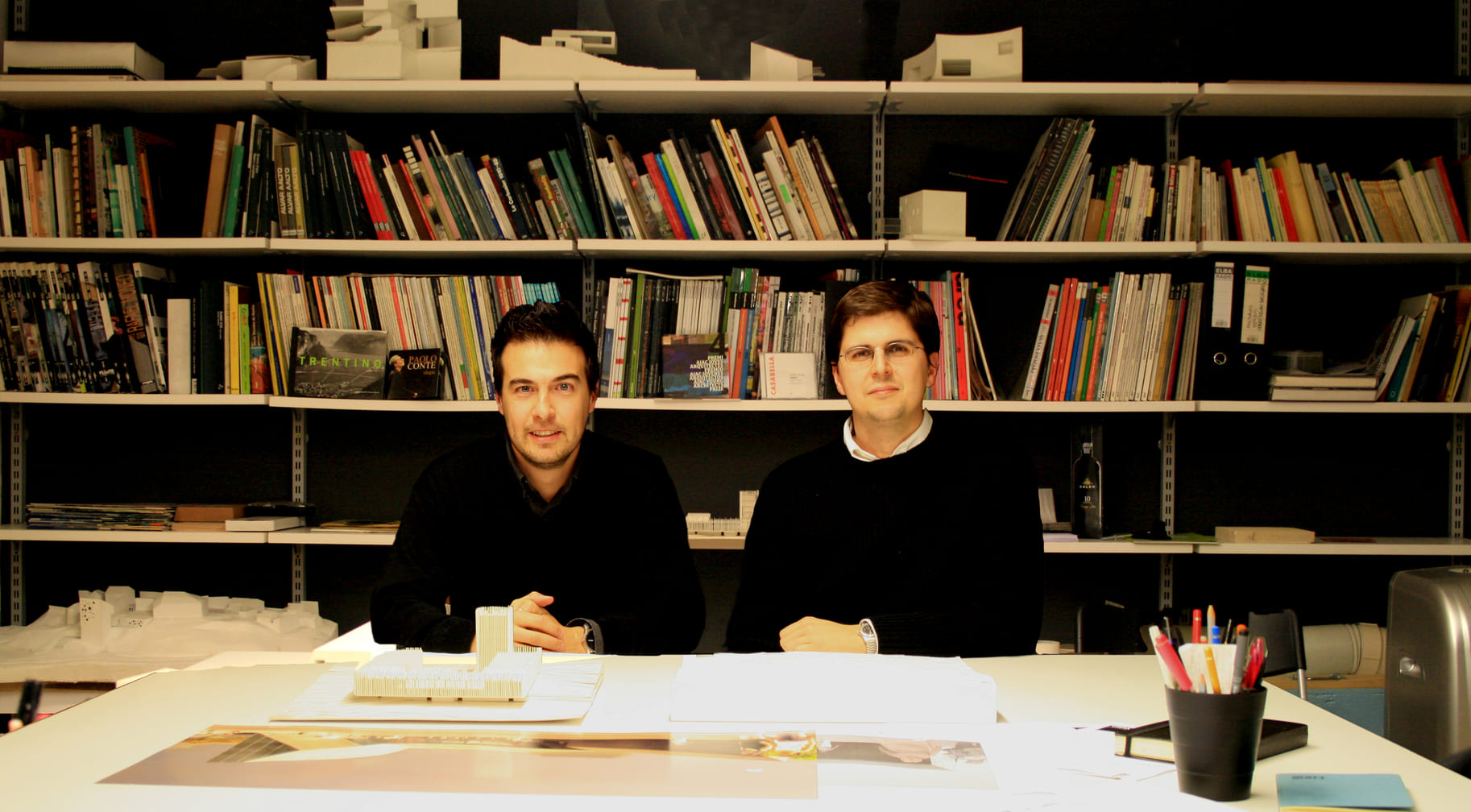

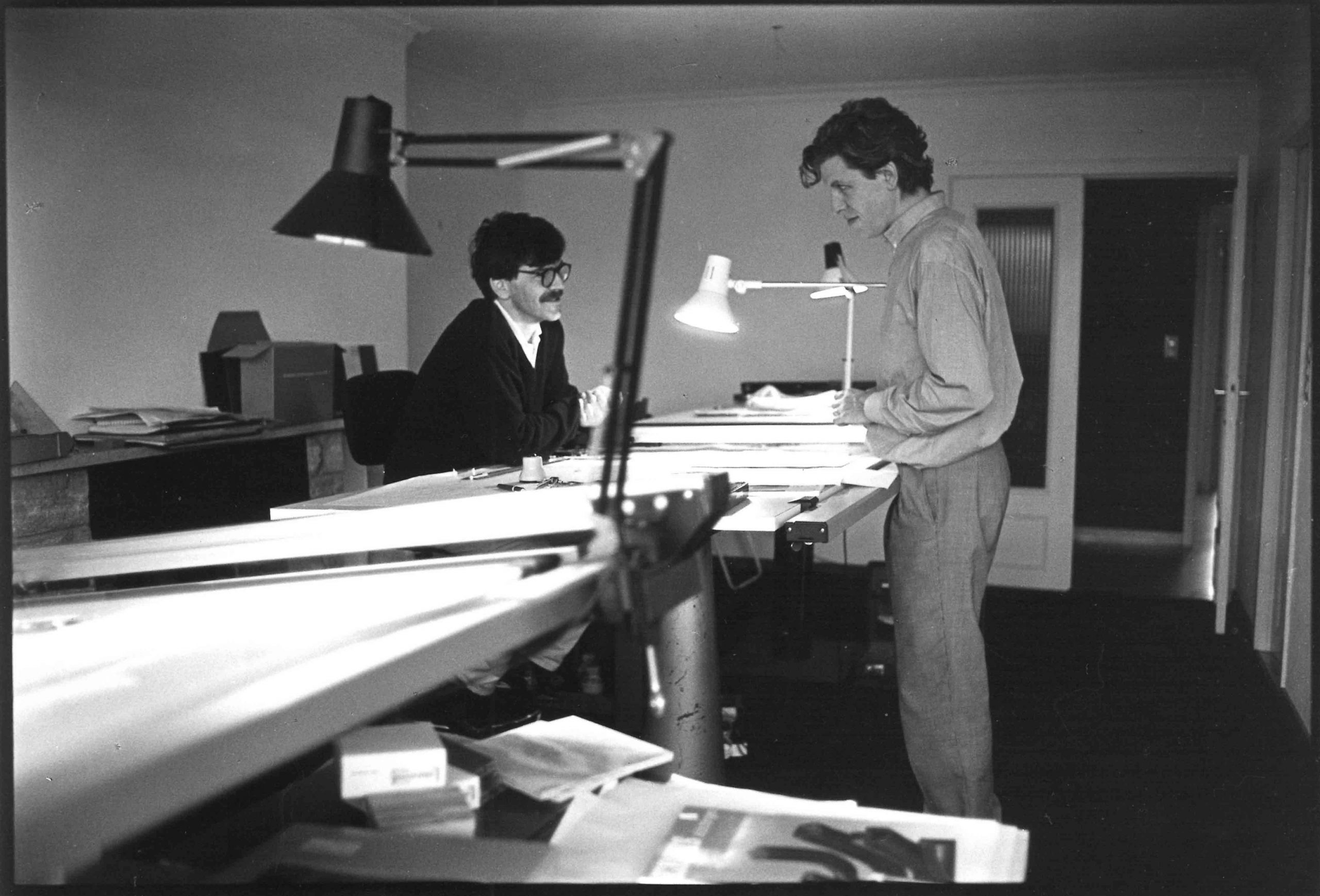

Atxu Amann, Andrés Cánovas and Nicolás Maruri. Image courtesy of Temperaturas Extremas Arquitectos

GV: How has the interest in the topic of gender evolved through the years in your career since the beginning of your PhD research? Could you also elaborate more on your PhD research and how the discussion of gender has changed from the past and thirty years on?

AA: When I first began, I had a similar format of research to that of this interview: first, the present, to analyse what is happening now; then going into the past to analyse how we have arrived at the present and finally, trying to make a prospective prediction to see what will happen in the future. Now, however, I believe that time is not a question of ‘Past’, ‘Present’, or ‘Future’ but time, as oriental civilisations understood, is the continuity of life. It’s very complex. Gender, on the other hand, is transversal in all my activities. I give many speeches about it and they always call me an activist. That means that I am not just involved in architecture. I work with violence of gender also in dwellings, or even to do away with some terms that remind us of gender, for example, ‘kitchen’. I don’t believe in ‘kitchen’, I don’t believe in ‘family’, I don’t believe in ‘dwelling’. I believe in domestic environments that have broken the walls of the dwelling. Now that the woman has left the dwelling, nobody pays attention to the children or the elderly, and the government is not prepared to do so either. Suddenly, many architecture typologies are growing spontaneously because old people have to be cared for by a team of professionals. The same with babies, because at six months, you have to leave them at home. There is a chaotic system caused due to the two revolutions of the twentieth century: the Information and Technology Revolution and the Women’s Revolution. If we reflect on it, we see that the future is going to be like the past. Women are going to be inside and men are going to be outside. We are not going to live inside and work outside. We are not going to work during the day and sleep at night. From studying gender, I have arrived at the philosophy that duality has been a strategy to control us. I don’t believe in duality. So what should we do now? I dedicate a lot of time with my PhD students to talk about duality as a strategy that must destroy. We work with the city like a domestic city, but also with the domestic space like a public space, with the virtual space like the material one. We don’t believe that the world is divided into women and men. We have 24 genders, like Facebook says, and it is important that we understand that from studying gender. Diversity is what is happening now in all the categories and so architecture cannot be ruled by the norms that depends on dualities: private and public, night and day, free and expensive. Gender has become a way to understand the world, perhaps a more human theory or approach that includes nature, machines and all the possibilities we have here.

GV: Although this approach is very urgent, does it feel that this is an isolated opinion in architecture? What should we do to make this topic and discussion more natural and common?

AA: Working in the university, I feel that I have a responsibility to help others understand these ideas more easily. Unfortunately, it is only when you get older that you really understand the world. It’s horrible because then, suddenly, you die. Now I am trying to fight against time in order to gain knowledge and disperse knowledge, looking for friends of the same thinking to sow some seeds to spread the knowledge more quickly. Moreover, time is accelerated now so you cannot wait and write an article; you have to move. Now, I have 20 PhD students and 200 other-year students. In their future, they will be able to continue developing these ideas. I really think that they are better than us. Students, now, are a different kind of people. Everybody speaks badly of them because they are connected to their phones the whole day but how can you not be connected? Even I am connected. I feel that the world today is divided. This digital break that everybody speaks about is a real break and here at the university, you can actually feel it. There are people who don’t feel the world and people who are in the world. The idea is to very quickly say those ideas and not be worried about it. The younger generation was born into it so they understand it. Just as how I understand the complex history of our times as I was born during Franco’s dictatorship.

GV: Do any interesting stories or anecdotes come to mind when you think of those beginning years?

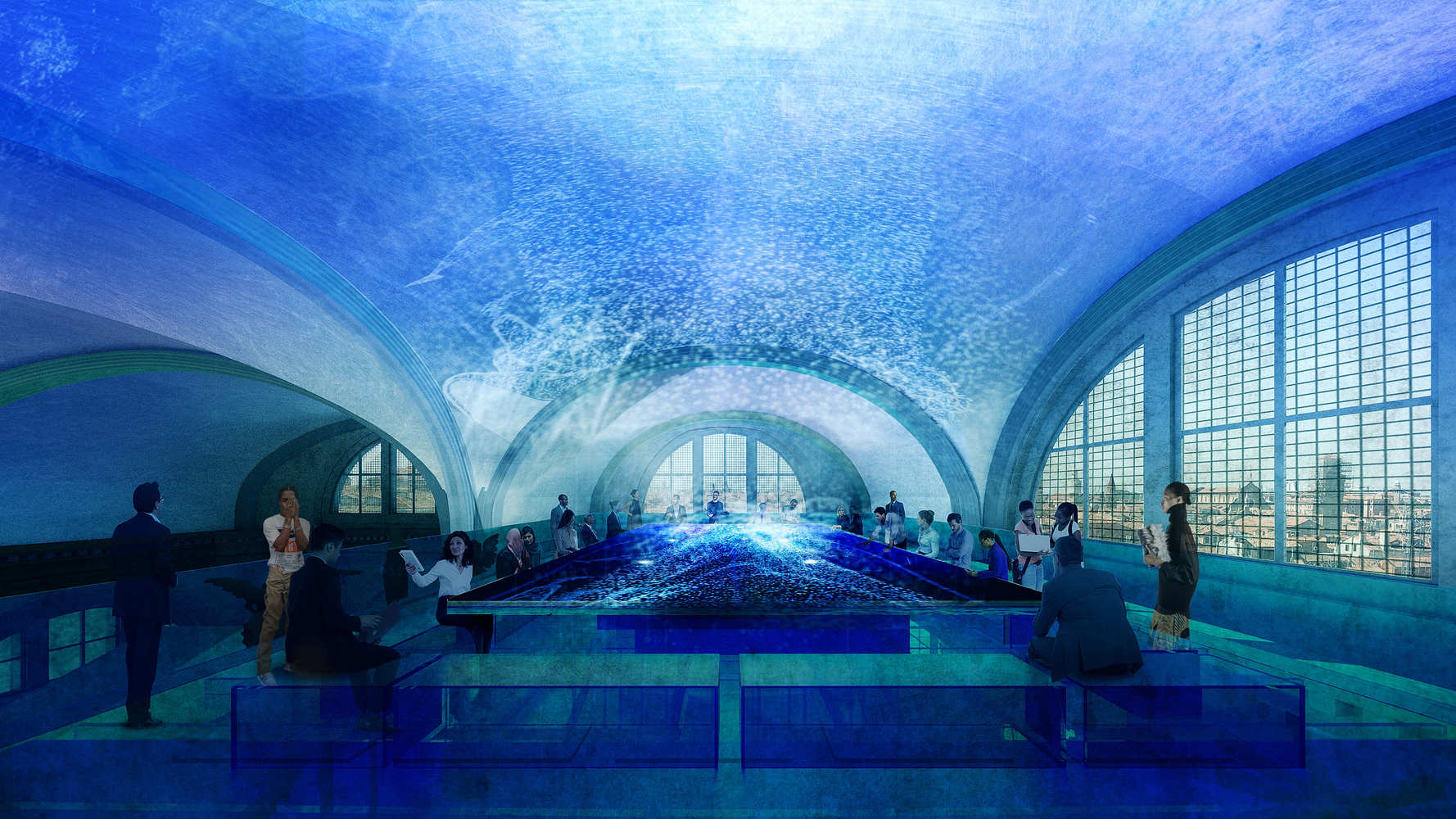

AA: What’s interesting is that I wasn’t very aware about the gender topic in the beginning. I lived among men, but it was natural. However, I do have another anecdote about our beginnings. We graduated in the year ‘87. Nicolás in May, myself in June and Andrés in September. However, in June, we won a scholarship with the European space programme to go to Darmstadt. We travelled through Germany in a very little car. We had gone to Germany with the aim of creating the first digital programme for architecture. However, it was horrible because we didn’t have any idea about it but we were the first ones who went there. Now people ask us, “Why did you enter a competition in Luxembourg, in Germany?” We have never been afraid. Failure was in our blood. In academia we had a lot of failure so it was no different for our professional careers. Three years later, we entered a competition in the Biennale of Architecture. There were not many computers at the time, but there were photocopiers and printers. We took some building from Mies Van der Rohe, cut them out, put them in a landscape format and presented this to the Biennale. We ended up winning the first prize. We couldn’t believe it but, to us, it was a very important moment. It was the first time that we understand that it was important to copy and to steal from the best. In that project, nothing was originally from us, except the decision to copy this skyscraper and to repeat it 9 times. In a way, we were provoking and working with the future. We became instrumentally advanced and had no problems working with Photoshop. In fact, in our first years, we earned our money working as graphic designers for IFEMA. We would design the magazine for the Spanish Architect. In the end, you are not just building but projecting and designing in other fields. That makes you very free to do anything: a wall, a table, or a building.